Dead in the water for more than half a century, the Kyle still has the power to summon the curious, which is how Dennis Flynn wound up viewing old slides of a legendary steamship with Heber McGurk.

The battered iron railing relinquishes remnants of paint akin to a snake shedding splotches of skin. They cartwheel out to sea under fair weather clouds, aloft on a gentle west wind. Along an upper deck, a carpet of green grass fingers upward to cover teak wood and metal flooring. High above, the crow’s nest has been commandeered by a brace of cormorants who gaze at me with studied indifference. Even after more than 50 winters since her demise, she’s still a sight to see.

The Kyle broke her moorings in a February 4, 1967, storm and ran aground on a bed of mussels at the Riverhead in Harbour Grace. Measuring 67 metres (220 feet) in length, 9.8 m (32 ft.) in width, and 5.5m (18 ft.) in depth, the 1,055-tonnes steamship was built in Newcastle-on-Tyne, England, by the firm of Swan Hunter and Wigham Richardson. She was launched on April 7, 1913.

Last year I visited with Heber McGurk, then 91, of Carbonear, NL, to talk about the SS Kyle. Heber worked aboard the Kyle from 1962 to 1965, and he has an incredible collection of colour slides taken with his camera during those last few years of her working life as a sealing vessel.

“I was Quartermaster and Master Watch, plus I did basically whatever was else was needed, including taking care of medical supplies and providing basic first aid,” says Heber. “My wife gave me a little camera and if there was anything interesting going on with the Kyle I’d take a few pictures so I could show her and my friends and family the slides when I got home.” Today, he’s offered to bring those slides out of storage and give me a rare look inside the famous Kyle.

While the old projector is warming up, Heber produces a small piece of notched wood and askes, “What would that be if you were writing home?”

I guess it must be some type of a tally stick for keeping track or score of something. “It is indeed a tally stick, but a very special type of one, and to the men on the ice it was definitely no game,” he said. “This was how they kept track of the seal pelts they harvested.” Heber’s tally stick was about 10 inches long and an inch square. A sealer would put a notch in one corner for every 25 seal pelts he put down in the hold of the vessel. Four notches carved in the tally stick meant 100 pelts.

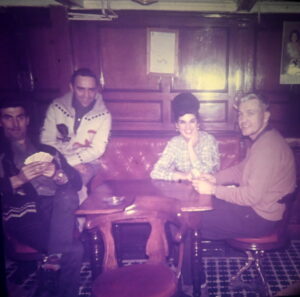

Finally images appear on the screen, and after an assortment of various boats and sealers at work on the ice fields, a photo pops up of several gentlemen having a game of cards in the saloon of the Kyle. “On this photo I can tell right away the sea is calm, since the table is relatively level and there are no metal rails in the centre of the table to hold the dishes in place.”

To prove his point, Heber shows me a similar photo on a much stormier day. The rails are there as he promised and the table is at a steep angle. Even simple tasks such as having a meal on rough waters took inventiveness.

When a photo slide taken in the iconic smokeroom on the Kyle (as commemorated in the famous 1950s radio play by Ted Russell) comes up, Heber identifies the photos in it as crewmember named Charlie; a lady named Inga and her husband Charlie Weir, a helicopter pilot; and the helicopter mechanic Roland Howell.

Heber explains, “Captain Guy Earle was pretty forward thinking, and he had a Spartan helicopter hired on a few seasons at the ice. This was a tremendous advantage in scouting and spotting the main herds of seals from the sky, and also in airlifting loads of pelts from a cable below the copter and landing them on the ice back near the ship. They would not drop the pelts directly on the Kyle decks because they were afraid the cable would get caught in the ship’s rigging, but it still beat hauling loads of heavy pelts long distances over the rough ice by hand.”

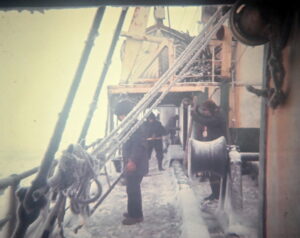

Particularly intriguing to me are the images from 1963 of the Kyle shrouded in ice from sea spray. “It was constant danger and effort to keep her clear during times of heavy ice buildup,” Heber notes. “It may not seem like too much of a problem sitting here in my living room now, but sometimes the ice would be so thick that a one-inch steel cable would become three or four inches thick. The extra weight could damage the ship, or pieces could fall off from up high and hit people. If we let it get too bad, it could even cause a ship to roll and turn over in a big sea. So, of course, we took to the task of beating it off as quick and safe as we could. With the lifeboats and davits frozen in there’d also be no way to launch a lifeboat, so we couldn’t allow that. The ice coating looks pretty in pictures, but it represented hard work and risk, and we were glad to be clear of it – even though it took the sealers nearly four days to carefully get it all off the Kyle that time.”

Another fascinating image Heber captured was when the Kyle came to the assistance of a large vessel, the Sir John Crosbie, in 1964. “The Crosbie was a big, grey, steel ship and carried her own helicopter on a platform on her stern deck. She got damaged somehow and was taking on water, so we came alongside and tied up and put men and pumps aboard. When she was finally fit to go, she managed to get back to St. John’s for repairs. But that was normal stuff and I know they would have done the same for us if we needed help.”

One final iconic image stays with me as I say my thanks to Heber and depart. It is the men of the Kyle standing in a semicircle on the barrack head near the bow in 1965, watching the icebreaker D’Iberville carve a path through a heavy floe for the Kyle to follow. Backs to the camera lens, faces forward and forever focused on the Great Front ahead, they remain ghosts of the Kyle who live on forever through the wonderful stories and slides of Heber McGurk.