Runaway Rooster

As a kid of nine years old, I recall waking up one warm Sunday morning in October to a soft breeze. I watched as it gently moved the curtains of my bedroom window, allowing the sound of distant church bells and crowing cocks to drift in.

A day of rest, where one could lie back knowing that chores like bringing two barrels of water for wash day were finished yesterday, and relax in anticipation of a special chicken dinner. This had turned out to be an exceptional year. Normally the only chicken we ate was on Christmas Day. This year we would have one for Thanksgiving. Dad said there was only room for one rooster at a time in any flock and the young one was the one to go.

The sudden change of habits by this young bird led me to believe that it had a sense of what was to come. Lately he had managed to cut a hen from the rest of the flock and was somewhat contented to at least have a sense of what life was about before making the supreme sacrifice. Just yesterday I had witnessed this gruesome execution. The sudden thud of Dad’s sharp axe embedding into the chopping block sent the victim’s bloody head – with eyes fixed wide open – straight to the ground and his trembling body floundering in the opposite direction. Unlike his lovesick hen, I never had the sense to avoid this barbaric act. But I’ll always remember the courage of that brave young bird, that seemed to actually stretch out his neck in anticipation of what was about to happen, and the emotionless look on Dad’s face will always be etched into my wind. Whooo! I still shudder at the thought of it.

The faint aroma of roasting chicken drifting up the stairs made it somewhat easier to force myself from the comfort of my feathered mattress, and I raced downstairs, washed and had a light breakfast of bread and tea.

Dinner finally arrived and I must say it was worth waiting for. Mom had lots of fresh veggies, salt beef, pease pudding and the whole nine yards, smothered in rich, brown gravy. The saying of grave in our house had a twofold purpose, one was to be thankful and the other was to remind us that we had evolved past the Neanderthal stage, which meant taking our time to make some attempt at chewing.

“Now that’s what you call a feed,” said Dad as he pushed back his chair and retreated to his favourite spot by the kitchen window. Mom and my sister fathered up the dinner scraps and instructed me to put them out for the hens. The scraps consisted of a variety of food bits with some tea leaves and corn thrown in for good measure. I thought this was a great gesture, a way of saying thank to for their contribution.

I opened the gate to our garden to find it practically empty except for one meandering hen that seemed to be looking for the young rooster. I thought maybe they were supposed to rendezvous at this particular end of the yard. Poor thing. The rest of our eighteen hens were out of sight down over the knoll, just a gunshot away. My first instinct was to call out, “here coup, coup, coup, coup,” but when I saw the lovesick hen, my heart went out to her, knowing the fate of her lost love. The least I could do now was offer her the solace of eating alone.

This Thanksgiving Day was so quiet and peaceful. I sat on the old chopping block, closed my eyes and absorbed the warm October sun along with the contented feeling a good meal brings.

A sudden cluck and flutter of wings quickly snapped my eyes open. A large rat had appeared out of nowhere and was now sharing the bits of scraps and corn I had placed there for the hens. Unprepared for this turn of events, I ran into the house calling “Dad! Dad! There’s a rat out eating the hens’ feed!” Dad was laid back in his armchair like an astronaut ready to blast off into the outer bowels of Dreamland. This trek was suddenly aborted as he sprang from his chair and went straight to the porch locker, returning with a muskrat trap, muttering to himself, “I’ll fix his flint.”

This particular trap had a killer bar which usually made short work of its victim. Dad always wore a cap to protect his head from sunburn, and this time he grabbed the nearest one on the rack, a stocking cap which he slung on his head as he ran out the door toward the garden. The rat had now retreated back to its hole, giving Dad time to carefully set the trap. He then got to his feet and gingerly spread extra crumbs over ground zero.

I guess I was about eight or nine years at the time, but he gave me stern orders not to let any hens near. This was a big responsibility for me and I did not take it lightly, and since there was only one hen nearby, I figured this would be an easy task. Dad was no sooner in the house when there was a sudden snap. The lovesick hen was in the trap, motionless. I thought she was dead and I knew I was to blame. I wasn’t quite sure if I should run for the hen or run for Dad. I couldn’t think straight, frightening thoughts raced through my mind – maybe the hen was still alive, and if so, who would Dad kill first? There were no answers. I took off for the house.

Dad was just reaching up to take off his cap and I swung the door open with a bang, screeching “there’s a hen in the trap!” He only had time to give me a hard look as he shot out the door. I followed behind at a safe distance. He quickly knelt down by the trapped hen and released the killer bar. She gasped for air and when she had her lungs full, the squawking came back as loud as if someone was actually killing her. What a racket. You could hear her up to Mouse Island. I felt a bit better now, knowing that she was alive. Now my sentence would probably be reduced from a felony to a misdemeanor.

Meanwhile, just out of sight down below the yard, our other rooster who was with the rest of the hens had picked up the loud calls of distress. Dad always called him ‘the Old General’ because he was the main kingpin and ruled the roost with an iron fist. This yard bird was generally quiet, but when someone crossed his forefoot, he was something to be reckoned with. This was such a time, and he came gum-booting up over the hill like a bat out of Hell. There was fire in his beady eyes as he paused momentarily to get his bearings then, seeing Dad with the squawking hen, he let out across the yard, his wings spread back and head tilted down like a concord, the last ten feet were airborne.

Dad was unaware what was about to happen because he was kneeling back-on during the final approach. It was a rough landing as the Old General came to a screeching halt on top of my father’s head, the force pushing him forward. The rooster drove the stocking cap down over Dad’s eyes and anchored it tight to his skull with his claws as he batted his wings furiously for solid footing and stability. Testosterone ruled the day. Dad dropped the hen and tried with two hands to get free of what he thought must have been the angel of Hell that had cowardly struck him from behind, drawn blood from his forehead and battered him with his wings in total darkness.

Finally he managed to dislodge the rooster from its grip and threw him to the ground. There was little doubt who had won the first round, but the match was far from over – very few had drawn blood Dad and he wasn’t about to extend the list. Dad’s face was red and sweaty, highlighting the emotional looks of rage and frustration as he thirsted for revenge. Old General had hit the ground running and had a head start around our house, but before his two white tail feathers floated to the ground, Dad and I were hot on his tail and the race was on. After two laps around our house without gaining on him, we realized the sharp turns were awkward when running counter-clockwise. We paused briefly to catch our breath and were reinforced with new runners, our serving girl, Carrie Ricketts, and Laddie, our dog. We started off again in the opposite direction. Laddie was in the lead followed by Carrie, then Dad, and myself bringing up the rear. Laddie passed the rooster, came to a halt, then just sat there on the sideline with a perplexed look on his face, as if to say, “what in Hell am I doing? I am not allowed to chase hens.”

Carrie was a young, vivacious maid of seventeen, just new at service work. She quickly gathered up her long frilly dress and held it above her knees, then took off like a deer. The gap was slowly closing and the rooster was looking for a way out. Then, seeing the open basement door, he quickly ducked inside. Now he was trapped. The only option was a puncheon that was inside which dad used to set broody hens. Carrie was right behind and followed him into the small opening, leaving just a small bit of her dress and ankles outside. I felt as if I should help this damsel in distress, but I was at a loss as to how I should go about it. Then dad came and without hesitation, drove him arm in the puncheon right up to his shoulder, gave his hand a twist, and pulled it out only to find a handful of tail feathers. He then helped Carrie up and they both laughed hysterically. This gave the rooster and me a golden opportunity to duck out the basement door unnoticed and fade back into the day that was to become one of my most cherished memories.

Lloyd Mushrow

Port aux Basques

Downhome no longer accepts submissions from users who are not logged in. Past submissions without a corresponding account will be attributed to Downhome by default.

If you wish to connect a submission to your new Downhome account, please create an account and log in.

Once you are logged in, click on the "Claim Submission" button and your information will be sent to Downhome to review and update the submission information.

Leave a Comment

MORE FROM DOWNHOME LIFE

Recipes

Enjoy Downhome's everyday recipes, including trendy and traditional dishes, seafood, berry desserts and more!

Puzzles

Find the answers to the latest Downhome puzzles, look up past answers and print colouring pages!

Contests

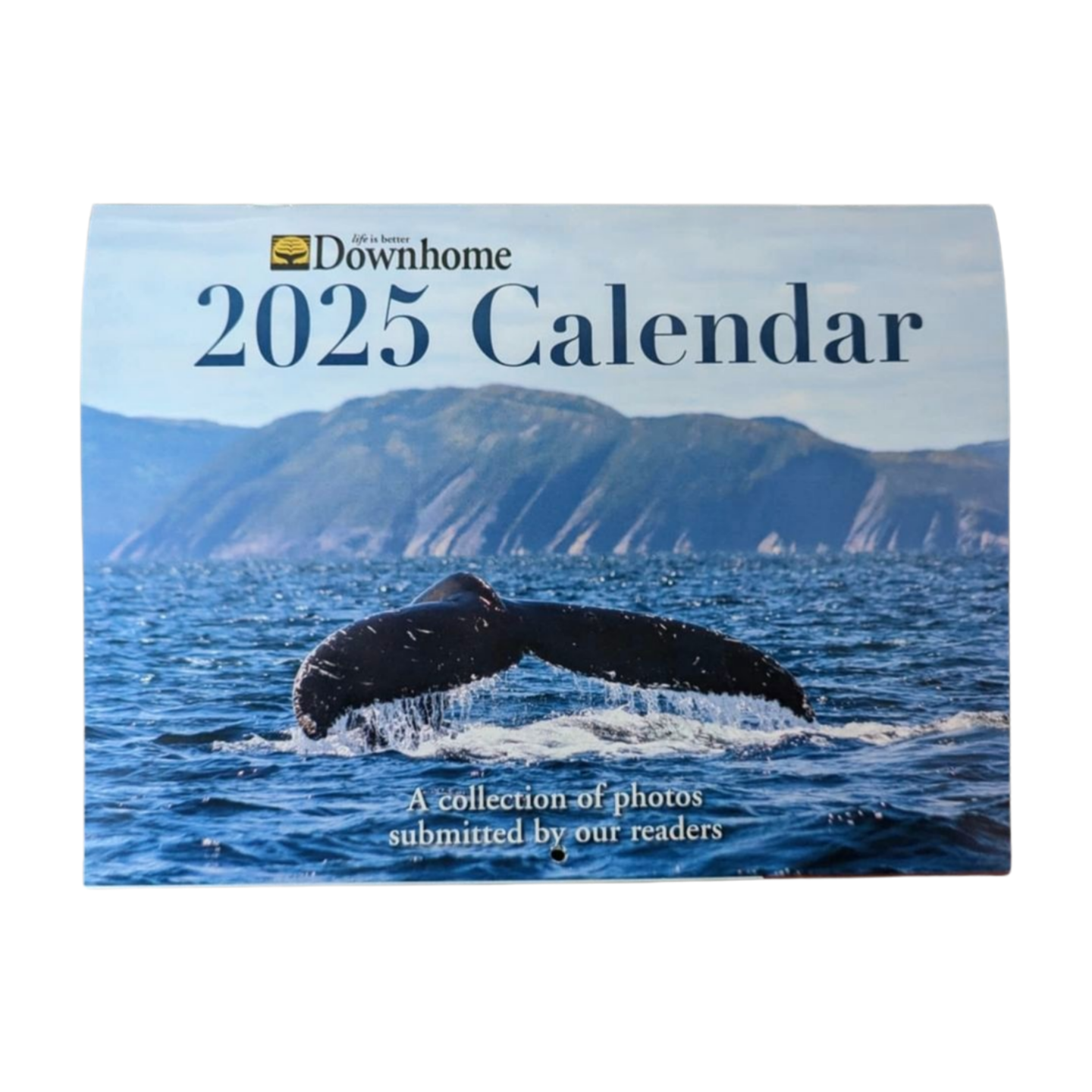

Tell us where you found Corky, submit your Say What captions, enter our Calendar Contest and more!